Stepwells are spiritual monuments dedicated to water, and a stark reminder of the increasing scarcity of this critical resource.

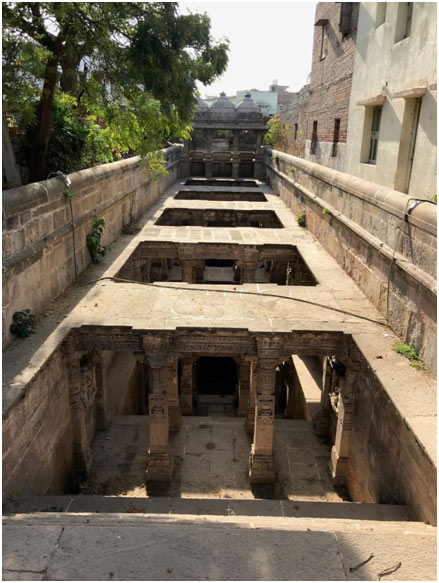

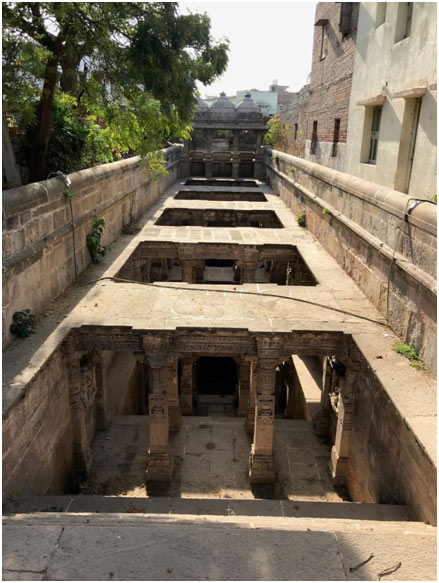

Stepwells, also referred to as “baoli”, “bawri”, “vav”, “kalyani” or “pushkari” constitute a unique part of Indian architecture, that are rapidly being forgotten. Essentially these are deep dug trenches or rock cut wells that are reached by a winding set of stairs or steps. The architecture varies from functional and utilitarian water sources to intricately carved and designed structures.

Divya Gupta, principal director of the architectural heritage division at INTACH notes, “In India, water has always played an integral part in architecture and city planning. The subcontinent has a long tradition of buildings connected with water… The connection between architecture and water is generally regarded as a connection between the secular and the sacred, between earth and heaven… Baolis, vavs or bawadis, as they are called in various parts of the country, are a building typology unique to the Indian subcontinent. They are testimony to the traditional water-harvesting systems developed in ancient times, and to the engineering and construction skills and the craftsmanship of those who built them.”

Construction:

Stepwells are largely present in Western India because of the dry semi-arid climate, notably Rajasthan and Gujarat, though they can also be found in abundance in Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka and Telangana. They came into being as sites at which to conserve rainwater during the monsoons, and keep it accessible during the rest of the year. Construction of stepwells included the sinking of a typical deep cylinder from which water could be hauled, as well as a carefully placed, adjacent, stone-lined “trench” that, once a long staircase and side ledges were embedded, allowed access to the ever-fluctuating water level which flowed through an opening in the well-cylinder. In dry seasons, every step – which could number over a hundred – had to be negotiated to reach the bottom story. However, during monsoons a parallel function kicked in, and the trench transformed into a large cistern, filling to capacity and submerging the steps sometimes to the surface.

This ingenious system for water preservation continued for over a millennium till the British arrived in India. The colonial administration deemed these structures, unhygienic, seeing them as breeding grounds for disease. They had little appreciation for the historic and cultural context and significance of stepwells. Many stepwells were destroyed or abandoned during this period, and local communities became disconnected from these spaces.

Architecture:

By building down into the earth rather than the expected “up”, a “reverse architecture” was created and, since many stepwells have little presence above the surface other than a low masonry wall.

Victoria Lautman, author of “India’s forgotten stepwells” notes: “It was like discovering a new species of mammal or a galaxy”. “I was taken to what was basically an unremarkable patch of desert, where there was a low wall in the distance. I was wondering: ‘What are we doing here, looking at a boring wall?’ But looking over this parapet, I confronted a deep, man-made chasm with a parade of carved columns and pavilions. It was completely unexpected, incredibly shocking, and subversive in that we’re conditioned to look up at architecture, not down into it. The experience of descending into this subterranean edifice, deep into the earth, was one of the most powerful experiences of moving through architecture that I’ve ever had. Still. Harsh sunlight became deep shadow, the heat in Gujarat was replaced by enveloping cool air, and the above-ground din disappeared into a pervasive hush. It was magical.”

The Gendered Politics of Stepwells:

Interestingly, a large number of stepwells are believed to have been commissioned by women – these include the famous world heritage site Rani kiVav, Rudabaikivava, and BaiHarirVav (commissioned by Queen Udaymati, Queen Rudadevi, and Baiharir, the superintendent of the household of Mahmud Begada, respectively). Rather than telling stories of men and war, as many monuments do – stepwells are associated with Mother Goddesses, who as deities, are associated with water and fertility.

Water as a resource is also closely associated with women – in many parts of the world, and in India, water collection is a task for women. Thus stepwells, which operate primarily as sources of water – formed a gathering space for women – to discuss, as well as to participate in rituals and communal activities. The development of stepwells as subterranean temples, and gathering spaces for women is therefore a natural evolution from the purely utilitarian.

Today:

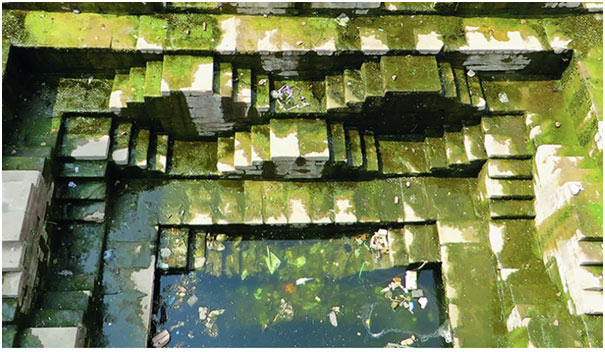

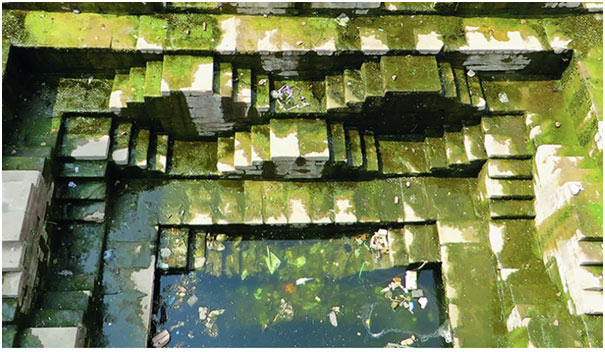

For centuries stepwells persevered as integral sources of water and sites of community gathering; they served as civic centres, refuges, remote oases, and, in many cases active places of worship. Thousands of the fascinating structures proliferated through the country between the 11th – 16th centuries. Today, however most are abandoned as a result of modernisation and neglect; many, especially those in cities, have fallen into disrepair or become the local garbage dump for the buildings and houses which come up around the structure. While some have been restored by the government, and repurposed into thriving centres (note ToorjikaJhalra in Jodhpur), most remain forgotten and in danger of extinction.

Do these unique structures have a future? With India’s growing water crisis, and the NITI Aayog estimating that twenty one cities including Delhi will run out of groundwater by 2020 – the urgency for water conservation in the country has spearheaded a few recent efforts to desilt and “reactivate” a few stepwells in Delhi and Gujarat in the hopes that they may once again become sites of to collect and store water. However, it is a long and slow process, and these architectural marvels seem to be vanishing into history.

References:

1. https://www.archdaily.com/395363/india-s-forgotten-stepwells/

2. https://www.livehistoryindia.com/amazing-india/2019/07/08/indias-water-crisis-a-dip-into-history

3. https://feminisminindia.com/2019/07/12/politics-water-space-and-religion/

4. https://scroll.in/magazine/832391/even-the-most-dilapidated-or-abandoned-stepwells-retain-the-essence-of-their-former-glory

5. http://www.caleidoscope.in/art-culture/ancient-indian-stepwells-show-us-the-way-to-conserve-water

Image Credits, MahilaBaagkiJhalra: https://scroll.in/magazine/832391/even-the-most-dilapidated-or-abandoned-stepwells-retain-the-essence-of-their-former-glory