Throughout the month of August, the Centre for Social Research is raising awareness about legal remedies available to women facing domestic violence, especially the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PWDVA), passed in 2005 and implemented beginning 26 October 2006. This Act has introduced necessary provisions that expanded previous legislation sanctioning domestic violence.

Prior to this Act, the only law protecting women from domestic violence was Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), initially passed in the wake of the Criminal Law Act of 1983 after a dalit, adivasi woman named Mathura was gang raped by two policemen in Maharashtra. §498A was intended to prevent harassment and violence against women specifically related to dowry, which was outlawed in the 1961 Dowry Prohibition Act. §498A criminalizes “any unlawful demand for any property or valuable security or is on account of failure by her or any person related to her to meet such demand.” Broadly conceived, however, 498A was the first section of the IPC to criminalize domestic violence, defined as “cruelty and harassment of a woman by her husband,” punishable by up to three years in prison.

Given the existence of §498A to protect women facing multiple forms of violence, why was the PWDVA then necessary?

§498A has several loopholes that PWDVA subsequently closed. PWDVA expanded provisions to women facing violence to women outside of formal marriages. These relationships, however, are still conceptualized as default heterosexual and the criminalization of homosexuality under §377 IPC continues to deny LGBTQ+ people their basic rights as citizens.

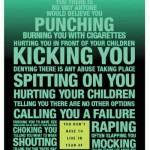

PWDVA also expanded its definition of violence to include not just physical but emotional, verbal, emotional, and economical abuse. The provision of verbal abuse has been criticized as diluting the bill’s more substantive measures by placing “‘name-calling’ related to not having a male heir” on equal footing as other forms of abuse (Gadkar-Wilcox 2012: 459). This wording also reifies the harmful notion that women are only ever victims of domestic violence, further entrenching a notion of violent masculinity that precludes men experiencing abuse from seeking help in the law.

Furthermore, §498A was highly controversial because its offenses were non-compoundable and non-bailable, leading to immediate arrests of anyone named by the aggrieved, including children, who were presumed guilty until proven innocent. §498A was amended in 2003 to make the offenses bailable and compoundable, but unfortunately the statute has become most commonly talked about by men’s rights activists who propagate an insidious paranoia that §498A gives women complete control over men. If you can stomach a horrendous amount of ignorance, merely glance at the first page of a Google search for 498A IPC.

About the Author

Hannah Carlan is a PhD student in anthropology at the University of California – Los Angeles, where she is researching discourses surrounding violence against women in India.

Looking forward to reading your blogs, you can mail us your entries at WriteWithUs@csrindia.org, or upload them at Write With Us.

Donation for Centre for Social Research to Join our effort in rehabilitating Domestic Violence

Discuss this article on Facebook